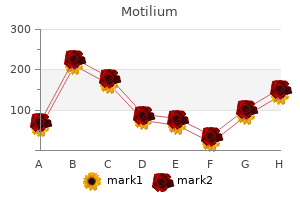

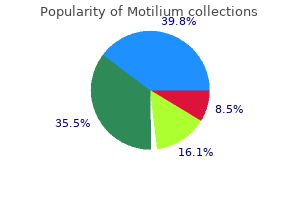

Motilium"Order motilium 10mg on line, gastritis xarelto". By: S. Cole, M.A., M.D. Deputy Director, Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin It is estimated that fermentation of carbohydrates in the colon is associated with a 50% reduction of energy content available for the body gastritis diet in pregnancy motilium 10mg amex, thus reducing the energetic value of carbohydrates from 4 to 2 kcal g-1. However, 31% of the patients in the acarbose group, compared to 19% in placebo group, discontinued treatment early, mainly due to gastrointestinal side effects [62]. About 50% more patients reported side effects on acarbose than on placebo, mainly flatulence, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Fifty-eight percent of the patients discontinued acarbose versus 39% drop-out in the placebo group. In conclusion, acarbose produces only a very modest (<1 kg), if any, weight loss and, taken together with its low tolerability due to prevalent gastrointestinal side effects, has no place in the treatment of obesity. Acarbose may, however, have some role in type 2 diabetics with a capacity to tolerate the compound [63]. Adverse effects the most frequent adverse effect is headache, but also dizziness, nausea, fatigue, urinary tract infections, dry mouth, and back pain are frequent side effects of lorcaserin. The majority of headache, dizziness and nausea effects occur early on in the course of treatment, tend to be mild to moderate, and generally do not recur after resolution of the initial event. Though lorcaserin has been associated with excess neoplasia or with evidence of hepatic toxicity in some rodent studies, there has been no evidence of this in humans. Lorcaserin does not cause clinically significant increases in serum prolactin, nor does it appear to increase the risk of cardiac valvular disease. Pharmaceutical compounds for diabetes treatment with weight loss properties Metformin Metformin is a biguanide that is approved for the treatment of T2D. It lowers plasma glucose by reducing intestinal absorption, suppressing hepatic glucose production, and increasing peripheral insulin sensitivity. The size of the placebo-subtracted weight loss induced by metformin in diabetics varies from 0. In this trial more than 1000 patients entered each treatment arm and the resulting high statistical power gives more credit to the outcome than those of smaller trials. Some of these analogues are being developed for both diabetes and obesity indications [65]. It was also found that obese individuals require higher doses than normal weight individuals to achieve the same degree of satiety, and that the satiety effect requires higher dosages than those required to obtain glucose lowering. Liraglutide has been assessed in a number of long-term trials in nondiabetic obese populations at doses up to 3. Liraglutide produced a dose-related weight reduction that was greater than placebo for all doses from 1. This trial was extended to 1 year, and subsequently all liraglutide and placebo patients switched to liraglutide 2. Liraglutide exerts beneficial effects on almost all clinically relevant cardiovascular risk factors, that is, blood pressure, blood Liraglutide 1. Change in body weight from screening over 2 years, presented as observed data Liraglutide 1. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 20-week study with 2-year extension in 564 obese patients. Participants received diet (500 kcal deficit per day) and exercise counseling during 2-week run-in, before being randomly assigned to once-daily subcutaneous liraglutide (1. Between 5262% of the liraglutide-treated individuals with prediabetes at randomization achieved normal glucose tolerance at year 2, compared with 26% of those on orlistat. This interpretation is supported by findings showing that weight loss with liraglutide 3. Most nausea/vomiting episodes started in the first 6 weeks of treatment, were transient, and were of mild or moderate intensity. Another cardiovascular side effect is an increase of 14 bpm after 1 year intervention. A possible mechanism for some of the cases of pancreatitis observed in the trials may be the triggering of acute pancreatitis among susceptible individuals, such as obese and type 2 diabetic subjects, by weight-loss induced gallstones. Efficacy A number of trials with the sustained release combination of naltrexone and bupropion, in combination with mild diet and exercise in overweight and obese subjects, have shown good efficacy in terms of weight loss as the combination produced a weight loss around 45% greater than placebo [73,74].

While the resemblance of oral Ra to the plasma glucose curve is evident (especially during the first 6090 min) gastritis quick cure purchase motilium canada, less appreciated is the fact that absorption is still incomplete 34 h after ingestion. Oral glucose elicits vasodilation of the splanchnic vascular bed; this, too, is a change that persists for at least 4 h [109]. Thus, both the metabolic and the hemodynamic perturbations induced by oral glucose extend beyond the time of return of plasma glucose to pre-ingestion levels. The tissue destination of absorbed glucose has been the subject of intense investigation. While the liver classically was reputed to be responsible for the eventual disposal of the majority of oral glucose [109], the weight of more recent evidence [33,36,110] favors the view that peripheral tissues are responsible for between one half and two thirds of glucose uptake, while the splanchnic tissues account for the remainder. A robust insulin secretory response directs more posthepatic glucose to the periphery, while a large increase in splanchnic blood flow increases the delivery of incoming sugar to the liver. The route of administration seems to influence the metabolic fate of glucose [33,36,113,114], in that the portosystemic glucose gradient per se enhances liver glucose uptake independently of portal glycemia and total glucose delivery to the organ [33,36,112,113] (as previously discussed). Insulin actions in vivo: glucose metabolism 229 250 Plasma glucose (mg/100 ml) 200 150 100 50 Oral glucose Total glucose Oral glucose Endogenous glucose augment hepatic glucose uptake, beyond its stimulatory effect on insulin secretion, has been proposed [122]. The inhibition of glucagon secretion and simultaneous stimulation of insulin secretion conspire to suppress hepatic glucose production. While glucose oxidation in the brain continues unabated during the absorptive period, some 50% of the glucose taken up by peripheral tissues (muscle) is oxidized, the remainder being stored as muscle glycogen or as lactate in the lactate pool [114]. During absorption, there is an increase in lactate release by both the splanchnic area as a whole and the intestine [2830]. In the latter, it has been estimated that some 5% of the ingested load is converted into three-carbon precursors of glucose (lactate, pyruvate, and alanine) and passed on to the liver [28,115]. The net release of lactate by the splanchnic area indicates that the sum of hepatic lactate production and gut lactate formation exceeds hepatic lactate extraction. Liver glycogen formation during absorption of oral glucose certainly occurs both directly from glucose and indirectly via gluconeogenesis. The relative contribution of the direct versus indirect pathway to hepatic glycogen synthesis is somewhat uncertain owing to methodological difficulties. Current data [116] suggest that gluconeogenesis participates in liver glycogen repletion to a lesser extent in humans than in rats [117,118]. Following glucose ingestion, the plasma insulin response is two- to threefold greater than that observed when the same glucose profile is created by intravenous glucose [119]. Since gastric emptying takes 1015 min to begin, it is clear that the nutrients cannot have reached the duodenum and certainly not the large bowel. Effects of fatty acids, ketone bodies, and pyruvate, and of alloxan diabetes and starvation, on the uptake and metabolic fate of glucose in rat heart and diaphragm muscles. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism 2002;282:E13601368. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2013;304:G11171127. These authors were aware that higher insulin after oral glucose implied insulin resistance, and suggested insulin resistance in obese patients, and patients with "maturity onset" (type 2) diabetes [7,8]. Kipnis reported a diminished plasma insulin response to a matched plasma glucose pattern in type 2 diabetic patients compared to nondiabetic patients [9]. Thus as of 1970, supportive evidence existed suggesting a defect in -cell function was responsible for "maturity onset" diabetes; au contraire, insulin resistance could likewise be implicated. Hyperinsulinemia in turn acts to renormalize the plasma glucose level by suppressing glucose production and increasing glucose utilization. In the presence of insulin resistance per se, the elevated insulin will be less able to normalize glucose, therefore resulting in a secondary stimulus to the cells and relative hyperinsulinemia. In fact, postprandial hyperinsulinemia was considered by Berson and Yalow to be the signature for insulin resistance [7,8]. Because of the closed-loop relationship between insulin secretion and insulin action it is problematic to infer the existence of insulin resistance directly from a "closed-loop" procedure such as the oral glucose Historical perspective the heralded isolation of insulin in Toronto in 1921 was followed immediately by treatment of diabetes. It soon became clear that while insulin was effective in regulating the blood glucose levels in most patients, there were some subjects in whom insulin appeared to be ineffective [1,2].

Tumor may also infiltrate the perivascular spaces gastritis flare up diet cheap motilium 10 mg fast delivery, causing the vessels within the mesentery to appear denser than the adjacent normal mesenteric fat. Obstruction of the small bowel is the most common complication of peritoneal carcinomatosis and may be secondary to diffusely infiltrating tumor or focal tumor masses. Because the normal peritoneum enhances to a similar degree as the liver, abnormal enhancement should be suspected when the peritoneum is enhancing more than the liver or has associated thickening, nodularity, or mass. Differential Diagnosis Malignant mesothelioma: Most common primary neoplastic lesion to diffusely involve the peritoneum. Evidence of asbestosis exposure such as pleural plaques helps to suggest the diagnosis over carcinomatosis. Lymphomatosis: Peritoneal lymphomatosis secondary to a preexisting lymphoma mimics peritoneal carcinomatosis and malignant mesothelioma. Extensive adenopathy in lymph node chains typically involved with lymphoma, such as those in the retrocrural region and small bowel mesentery, may suggest lymphomatosis over carcinomatosis. Tuberculous peritonitis: May have a similar appearance to malignant mesothelioma and peritoneal carcinomatosis but can also show evidence of ileocecal tuberculosis or low-attenuation lymph nodes in the small bowel mesentery, peripancreatic region, or retroperitoneum. Mechanisms of Tumor Spread to the Peritoneum Gastrointestinal and ovarian malignancies spread to the peritoneum when tumor grows through the entire thickness of the wall of the bowel to the peritoneum or extends through the peritoneal lining of the ovary, pancreas, or 662 Gastrointestinal Imaging liver. Secondary seeding of the peritoneum occurs iatrogenically during surgery or biopsy when there is tumor spillage into the peritoneal cavity. Tumor emboli can also reach the peritoneal cavity from surgically divided lymphatic channels or the dissected margin of the surgical site. Direct invasion into the peritoneum occurs through contiguous extension of gastrointestinal primary malignancies or tumor extension through the peritoneal ligaments and mesenteries. Extra-abdominal primary malignancies such as melanoma and breast and lung carcinomas spread to the antimesenteric border of the intestine and peritoneum hematogenously. Lymphatic dissemination is thought to play a minor role in the spread of gastrointestinal malignancies to the peritoneum. Key Points In patients with new-onset ascites, loculation of ascitic fluid is one of the most helpful features helping to differentiate malignant from benign ascites. Occult carcinomatosis may be located in the dependent recesses of the peritoneum: pouch of Douglas or retrovesical space, ileocecal region, paracolic gutters, subhepatic space, right subdiaphragmatic space, and root of the small bowel mesentery. Pathology Grossly pseudomyxoma peritonei is characterized by mucinous ascites and gelatinous material covering the peritoneum. It tends to spare the peritoneal surfaces of the bowel and accumulate in the subphrenic and subhepatic spaces, along the omental surfaces, and in the gravity-dependent portions of the pelvis. Histologically the mucin pools contain tumor cells that tend to be cytologically bland rather than frankly malignant. Collagenous tissue may be admixed with the mucin or extend through the lobules of omentum. Imaging Features Abdominal radiographs are not used to diagnose pseudomyxoma peritonei, but they may be obtained when a patient complains of abdominal distention. Radiographically pseudomyxoma peritonei produces increased opacity throughout the abdomen with poor definition of the intra-abdominal organs and obliteration of the psoas margins when extensive mucin is present. Sonographically pseudomyxoma peritonei can be suggested when ascitic fluid is echogenic, indicating that the fluid is gelatinous. The echoes within pseudomyxoma peritonei are nonmobile, in contrast to mobile echoes in ascites that contains debris or proteinaceous exudate. Scalloping of the hepatic and splenic margins may be observed if the serosal surfaces are well imaged. Early or recurrent mucinous deposits of pseudomyxoma peritonei accumulate in the dependent areas of the peritoneal cavity. This is an important diagnostic finding that differentiates pseudomyxoma from simple ascites. Differential Diagnosis Mucinous carcinomatosis: Peritoneal carcinomatosis from a high-grade mucinous carcinoma may be difficult to differentiate from true pseudomyxoma peritonei because the imaging features overlap. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Definition Pseudomyxoma peritonei is the clinical or radiologic finding of copious, thick mucinous or gelatinous material on the surfaces of the peritoneal cavity. The majority of cases of pseudomyxoma peritonei develop from peritoneal spread of low-grade mucinous carcinomas arising in the appendix that penetrate or rupture into the peritoneal cavity. Demographic and Clinical Features Pseudomyxoma peritonei is rare, occurring more commonly in women than men (mean age 49 years). Patients may complain of progressive abdominal pain, increasing abdominal girth, and weight loss.

Thus gastritis diet ���� order 10 mg motilium visa, a primary action in increasing fructose 2,6-bisphosphate in the liver with subsequent stimulation of glycolysis and inhibition of gluconeogenesis, although of interest, is unlikely to be a significant component of sulfonylurea antidiabetic action. Sulfonylureas and meglitinides: insights into physiology and translational clinical utility 623 Effects on insulin action An extrapancreatic action of sulfonylureas that may have a meaningful antidiabetic effect is the potentiation of insulin action. The clearest demonstrations of sulfonylurea potentiation of insulin action have been carried out in animal models. Experiments utilizing in vitro mouse diaphragms or organ cultures with rat adipose tissue have demonstrated that ordinary doses or concentrations of sulfonylureas potentiate insulin-mediated 2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake following a latent period of about 12 h [60]. One study suggested that this is attributable to sulfonylurea potentiation of insulin-mediated translocation of the glucose transporter from intracellular storage sites to the plasma membrane [61]. The chronic treatment caused no significant alterations in plasma glucose or insulin. Some show that sulfonylurea treatment increased insulin-mediated glucose disposal, but only in patients who have increased insulin secretion [63]; the improved glucose disposal is attributed to higher plasma insulin levels. In a study on insulin-treated type 2 diabetic subjects who had little or no remaining endogenous insulin, sulfonylurea failed to evoke any glucose reduction [64]. Other studies show that sulfonylurea treatment increases insulin-mediated glucose disposal, but the improvement was attributed to the effect of better glycemic regulation. Sulfonylureas have been reported to potentiate insulin-mediated glycogen and lipid synthesis. Clinical studies suggest that the reduction in fasting hyperglycemia during sulfonylurea treatment can be attributed in part to potentiation of insulin action on glycogen synthesis and gluconeogenesis [64]. Detailed discussions of the relative roles of pancreatic versus extrapancreatic mechanisms in the antidiabetic action of sulfonylureas are available in several reviews [57,67]. The mechanisms of the various extrapancreatic actions of sulfonylureas have not been defined. They have not been found in liver cells and are present in very minimal quantities in skeletal muscle cells. There is no evidence to suggest that ionic fluxes have any role in mediating the extrapancreatic effects described. The insulin-potentiating action of sulfonylureas has a latent period of several hours, and this effect is blocked by cycloheximide, indicating that new protein synthesis may be necessary for that effect to occur [68]. The effect of sulfonylureas in potentiating insulin action on muscle, adipose tissue, and liver has raised the issue of whether these effects are mediated by a direct action in increasing insulin binding by the insulin receptor (an increase either in receptor number or in affinity) or through post-receptor mechanisms. Studies in vivo in which insulin binding is assessed are invalid to answer this question because changes in plasma insulin levels will influence the number of insulin receptors, and measurements of insulin binding to circulating monocytes or adipose tissues may not reflect what is occurring at liver and muscle cells. Assessment of insulin binding to fibroblasts in culture has little physiologic meaning. Several studies in vitro indicate that the effect occurs at a post-receptor site [57]. Effect on systemic availability of insulin One of the earliest extrapancreatic actions of sulfonylureas to be described was inhibition of insulinase, particularly in the liver [69]. However, several recent studies suggest that at least glipizide [70,71] and glibenclamide [72] increase the systemic availability of insulin through reduction of the hepatic extraction of insulin secreted from the pancreas. It is not known whether the effect is a primary one, for example inhibition of hepatic insulinase or displacement of insulin from hepatic binding sites, or is secondary to the increased rate of insulin secretion subsequent to sulfonylurea stimulation of the cells [71]. If the increased systemic availability were attributable to displacement of insulin from hepatic insulin receptors, it is also possible that such displacement may reduce the effect of insulin exerted on the liver and hence would lead to an increased hepatic output of glucose, provided that the displacement was extensive enough. Such a phenomenon would help to explain why high doses of sulfonylurea may impair instead of improve blood glucose control [73,74]. Effects on blood lipids Sulfonylurea treatment has been reported to have beneficial, neutral, or adverse effects on blood lipids [5,6]. It seems unlikely, therefore, that sulfonylureas have direct effects on very low-density lipid triglycerides, low-density lipid cholesterol, or high-density lipid cholesterol. Effect on fibrinolysis A recent study on bovine aortic endothelial cells indicated that certain sulfonylureas may enhance fibrinolysis and that the fibrinolytic mechanism is associated with sulfonylurea-enhanced production of plasminogen activator [75]. Differences in extrapancreatic effects Some extrapancreatic effects of sulfonylureas are related to parts of the molecule other than the sulfonylurea core and are 624 Chapter 42 therefore unrelated to the antidiabetic action. Buy 10 mg motilium fast delivery. RANITIDINE 150 mg tablet use side effects (Medi talks # 10) In hindi with ALL MEDICINE.

|