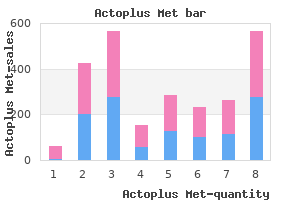

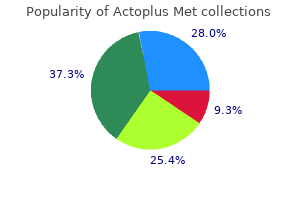

Actoplus Met"Effective actoplus met 500mg, diabetes prevention guide". By: D. Lisk, MD Vice Chair, University of Colorado School of Medicine Sirikulchayanonta V diabetes 101 buy 500 mg actoplus met, Jaovisidha S: Soft tissue telangiectatic osteosarcoma in a young patient: imaging and immunostains. Vanel D, Tcheng S, Contesso G, et al: the radiological appearances of telangiectatic osteosarcoma: a study of 14 cases. Wines A, Bonar F, Lam P, et al: Telangiectatic dedifferentiation of a parosteal osteosarcoma. Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Fabbri N, et al: Osteosarcoma: low-grade intraosseous-type osteosarcoma, histologically resembling parosteal osteosarcoma, fibrous dysplasia, and desmoplastic fibroma. Longhi A, Fabbri N, Donati D, et al: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma: results in eleven cases. Mahajan S, Juneja M, George T: Osteosarcoma as a second neoplasm after chemotherapeutic treatment of hereditary retinoblastoma: a case report. Ottaviani G, Jaffe N: Clinical and pathologic study of two siblings with osteosarcoma. Iemoto Y, Ushigome S, Fukunaga M, et al: Case report 679: central low-grade osteosarcoma with foci of dedifferentiation. Bacci G, Fabbri N, Balladelli A, et al: Treatment and prognosis for synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma in 42 patients. Chauveinc L, Mosseri V, Quintana E, et al: Osteosarcoma following retinoblastoma: age at onset and latency period. Sato H, Hayashi N, Yamamoto H, et al: Synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma involving the skull presenting with intracranial hemorrhage: case report. Doganavsargil B, Argin M, Kececi B, et al: Secondary osteosarcoma arising in fibrous dysplasia, case report. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery, Atlanta, February 1988. Hoshi M, Matsumoto S, Manabe J, et al: Malignant change secondary to fibrous dysplasia. Rosemann M, Kuosaite V, Nathrath M, et al: the genetics of radiation-induced and sporadic osteosarcoma: a unifying theory Shuhaibar H, Friedman L: Dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma with high-grade osteoclast-rich osteogenic sarcoma at presentation. Campanacci M, Giunti A: Periosteal osteosarcoma: review of 41 cases, 22 with long-term follow-up. Cesari M, Alberghini M, Vanel D, et al: Periosteal osteosarcoma: a single-institution experience. Hoshi M, Matsumoto S, Manabe J, et al: Three cases with periosteal osteosarcoma arising from the femur. Hoshi M, Matsumoto S, Manabe J, et al: Report of four cases with high-grade surface osteosarcoma. Bertoni F, Present D, Hudson T, et al: the meaning of radiolucencies in parosteal osteosarcoma. Futani H, Okayama A, Maruo S, et al: the role of imaging modalities in the diagnosis of primary dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma. Hoshi M, Matsumoto S, Manabe J, et al: Oncologic outcome of parosteal osteosarcoma. Picci P, Campanacci M, Bacci G, et al: Medullary involvement in parosteal osteosarcoma: a case report. Picci P, Gherlinzoni F, Guerra A: Intracortical osteosarcoma: rare entity or early manifestation of classical osteosarcoma Fang Z, Yokoyama R, Mukai K, et al: Extraskeletal osteosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of four cases. Enchondroma is an example of a benign cartilage neoplasm that most frequently occurs within the medullary cavity. It rarely presents as a bone surface subperiosteal (juxtacortical) lesion such as a periosteal chondroma. Diseases

C diabetes in dogs caninsulin purchase actoplus met 500mg visa, Intermediate power photomicrograph of osteoblastoma with irregular bony trabeculae surrounded by prominent rims of osteoblasts. D, Higher power view shows prominent osteoblastic cells bordering irregular poorly mineralized bony trabeculae. A, Irregular haphazardly arranged bony trabeculae of woven bone surrounded by plump osteoblastic cells in a highly cellular spindle cell stromal tissue with dilated vessels. C, Small focus of lacelike poorly mineralized osteoid with entrapped osteoblastic cells. D, Small focus of ill defined osteoid deposition with entrapped osteoblastic cells. A, Unusual case of osteoblastoma with area of well-developed cartilage in otherwise typical osteoblastoma. A, Low power photomicrograph shows well-developed haphazardly oriented trabeculae of bone in hypercellular stroma with atypia. C and D, High power photomicrographs of bony trabeculae in stromal tissue showing prominent atypia. Note the degenerative nature of atypia and the absence of mitotic activity in this osteoblastoma with pseudosarcomatous change. Radiographic Imaging Aggressive osteoblastomas share many of the radiographic features of conventional osteoblastoma. The main difference from conventional osteoblastoma is that aggressive osteoblastomas are larger, usually exceeding 4 cm in diameter. The lesions of long bones and the skull may have a distinct rim of moderate sclerosis. In small anatomic structures (vertebral column, bones of the hands and feet), the lesion may cross a joint space to involve the adjacent bone, providing clear evidence of its local aggressive nature. In some cases, prominent periosteal new bone formation can be present, raising the radiologic suspicion of malignancy. These tumors are likely to recur, do not metastasize, and are characterized microscopically by the presence of so-called epithelioid osteoblasts. Transition to osteosarcoma has not been observed to date, and these rare tumors therefore are not considered to be precursors of conventional osteosarcoma. Incidence and Location this is a very rare tumor, and its true incidence and its age distribution are not exactly known. The original series, reported in 1984, consisted of 15 cases,39 and an update published in 199641 dealt with 21 additional cases of aggressive osteoblastoma. A further 11 cases observed as consultations since 1996 are included in the present chapter. The limited experience with these tumors based on the analyses of 47 cases indicates that they occur in a slightly older group of patients than conventional osteoblastomas. The ages of 47 patients with aggressive osteoblastoma ranged between 7 and 80 years. This indicates that the overall distribution pattern of aggressive osteoblastoma is similar to that of conventional osteoblastoma, with clear predilection for the axial skeleton. The second most frequent location of occurrence is in the small bones of the hands and feet. This distribution pattern is clearly different from that of conventional osteosarcoma, further supporting the close pathogenetic relationship between aggressive osteoblastoma and conventional osteoblastoma. Aside from the personally collected series reported here and based largely on consultation material, the recent literature contains individual case reports of these very rare tumors. Similar to conventional osteoblastoma, it may bleed profusely during curettage because of its rich stromal vasculature. The bone contour can be markedly expanded with a thinned and focally disrupted cortex.

Thus clinicians should continually monitor patient compliance diabetes test name purchase 500 mg actoplus met visa, potential benefit, and potential complications in patients in whom thickened liquids are used as a therapeutic intervention. Additional Effects of Thickened Liquids on the Swallow Mechanism Thickening liquids also may affect swallow physiology. For example, increasing liquid viscosity has been shown to increase lingual-palatal contact pressures during swallowing by healthy volunteers. However, aside from timing alterations, few studies have evaluated bolus accommodation to varying liquid viscosities in adults with dysphagia, and at least one study has suggested that increasing liquid viscosity did not affect the timing or bolus propulsive force of swallows performed by adults with neurogenic dysphagia. Given the prevalence of liquid modifications in clinical management, the effect of thickening liquids on swallow physiology in adult patients seems an important area of clinical investigation. Carbonated thin liquid resulted in less penetration into the airway than noncarbonated thin liquid, faster pharyngeal transit than thick liquid, and less residue than thick liquid. However, unlike the prior study, no timing differences resulted from use of carbonated liquids. Furthermore, patient acceptance of carbonated liquids was high with only a single patient reporting dislike for this fluid. Krival and Bates46 reported that carbonated liquids result in greater lingual-palatal pressure traits during swallowing in healthy adult women. However, they reported no significant effect of carbonated beverages on pharyngeal reaction time or muscle activation. They interpreted reduced laryngeal elevation duration in older subjects to reflect improved swallow physiology. Like Krival and Bates,46 these investigators identified chemesthesis from carbonic acid in the beverage as a direct sensory nerve stimulant that may facilitate swallow changes. These findings are intriguing, but clinicians must remember that these studies, like those described in the preceding section, evaluate the immediate effect of carbonated liquids during the fluoroscopic or other physiologic swallowing examinations and do not necessarily translate directly into a proven benefit from use of carbonation as a treatment approach. Taste may be another bolus characteristic with the potential to affect swallowing performance. In a comparison of a sour bolus (50% lemon juice and 50% barium liquid) with a regular barium bolus they reported that patients with neurogenic dysphagia demonstrated faster oral onset of the swallow (all patients), decreased pharyngeal delay (stroke patients), and reduced frequency of aspiration (other neurogenic causes). Subsequently, Pelletier and Lawless49 evaluated the effect of citric acid (a sour bolus) and citric acid plus sucrose (a sweet-sour bolus) on the swallowing performance of nursing home residents with dysphagia. Additional studies of the effect of taste stimuli on swallowing have focused on healthy volunteers. Finally, Pelletier and Dhanaraj52 reported that moderate sucrose (sweet) and high citric acid (sour) and salt concentrations resulted in significantly higher lingual swallowing pressures compared with water. These effects were more pronounced with thicker liquids such as honey-thick consistencies. This observation might help explain the dislike of thick liquids, especially thicker liquids, by adult patients with dysphagia. Available evidence does indicate a reduction of aspiration rates in groups of patients when thin liquids are thickened to nectar or honey consistencies during the fluoroscopic swallowing study. Remember that the recipient of thickened liquid strategies is the patient with dysphagia. Available evidence indicates increasing dislike for thick liquids as the degree of thickness increases. Also, limited patient compliance research suggests that nearly 50% of patients prescribed thick liquids do not actually use them routinely. Clinicians should also consider other liquids modifications such as carbonation and taste variations when contemplating liquid modification as a component of dysphagia management. Texture-Modified Diets Similar to liquids, foods may be modified to accommodate perceived limitations in swallowing function in adults with dysphagia. Patients who had been treated for oral cancer were monitored over a 6-month period. These clinical observations suggest that patients will self-modify diet items that are difficult to swallow. However, despite the optimism depicted in these early clinical descriptions, more recent clinical research has raised questions about the nutritional adequacy of modified diets. These investigators speculated further that other nutrients may also be deficient as a result of the texture-modified diet.

In some unusual instances gestational diabetes test instructions buy actoplus met american express, it may occur many years after the removal of the primary tumor. In the past, radiation therapy was frequently used to control the disease locally and has been proved to be effective in preventing local recurrences. Because the majority of malignant transformations in giant cell tumor are linked to prior radiation, radiotherapy is no longer recommended as a primary mode of treatment. Typically the pulmonary nodules grow slowly and are amenable to surgical excision with a prospect for cure. A, Radiograph of knee of 17-yearold skeletally mature girl with a 6-month history of knee pain whose giant cell tumor involved lateral half of tibial plateau; subchondral bone was curetted and bone grafted. D, Histologic appearance of recurrent giant cell tumor is identical to primary neoplasm. A, Radiograph of knee of a 27-year-old woman shows eccentric lytic tumor on medial side of tibial plateau. B, Eighteen months later patient returned with palpable nodule in soft tissue beneath surgical scar (arrows) with peripheral calcification seen on radiograph. E, Photomicrograph of recurrent tumor nodule with peripheral shell of reactive bone. Development of sarcoma in conventional giant cell tumor is the most serious complication but fortunately is rare. As mentioned previously, the majority of secondary sarcomas that arise in association with conventional giant cell tumor are linked to prior radiation therapy. With the decline in the use of therapeutic irradiation for giant cell tumors, malignant transformation has become exceedingly rare. Special Techniques It appears that several cell types that belong to the macrophage/osteoclastic and osteoblastic lineages contribute to the development of giant cell tumors. Ultrastructurally, the cytoplasm of mononuclear cells contains abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum, moderate numbers of mitochondria, a few lysosome-like bodies, and occasionally multiple lipid vacuoles. In summary, the ultrastructure is of little help to elucidate various dilemmas related to the origin of a giant cell tumor. It suggests, however, that the mononuclear cells have some ultrastructural similarities with cells of histiocytic lineage, macrophage lineage, or both. In fact, some of the mononuclear cells express the receptor for the immunoglobulin G crystallizable fragment and differentiation antigens associated with a macrophagemonocyte lineage. The cells of monocytemacrophage lineage do not proliferate well in vivo and are usually eliminated from tissue culture explants. In summary, the main population of cells in giant cell tumor have phenotypic features of both macrophage-like and osteoclastic cells. Gly34Trp change in the majority of cases were found in approximately 90% of giant cell tumors. Little is known about the factors governing local aggressive behavior, recurrence rate, and metastatic potential of conventional giant cell tumors. This does not correlate with the clinical behavior of the lesion and cannot be used as a reliable factor for predicting recurrence or pulmonary metastases. Allelic losses of 1p, 9q, and 19q are frequent in giant cell tumors but do not correlate with local recurrence or metastatic potential. D, High proliferation rate documented by positive immunohistochemical staining for Ki67. The key to distinguishing these lesions is in the unswerving adherence to clinicoradiologic correlation to arrive at a diagnosis. Generally, a diagnosis of giant cell tumor is suggested by the presence of a radiolucent lesion in the end of a long bone or an equivalent epiphyseal site in a skeletally mature individual. Other common locations include the sacrum and "epiphyseoid" bones, such as the carpal and tarsal bones and the patella. The true giant cell tumor, for practical purposes, does not arise in the craniofacial skeleton, and it very rarely develops in nonepiphyseal locations. The short tubular bones of the hands and feet present a particular problem because of the morphologic overlap with giant cell reparative granuloma, which has a predilection for this skeletal site. In this situation, attention to the specific site of involvement with respect to epiphyseal location and skeletal maturity is particularly important. Perhaps the most important problem in histologic recognition of true giant cell tumor is created by the tendency for this tumor to undergo fibrohistiocytic reactive changes that can simulate benign or malignant primary tumors of fibrohistiocytic origin. Actoplus met 500 mg low cost. How to Reverse Diabetes & Lose Weight/Belly Fat in 10 Steps Segmt 2 of 5.

|